This year has thrown some curveballs our way, but it has also required us to pause, think about what we want our future to look like and reset accordingly. For National Recycling Week this year we are looking ahead to our Future Beyond the Bin, where materials remain in circulation and what was once seen as waste is understood as resource. To that end, we are asking Australians from all walks of life to share their inspiring stories of how they #gobeyondthebin at work, home, school and in the community.

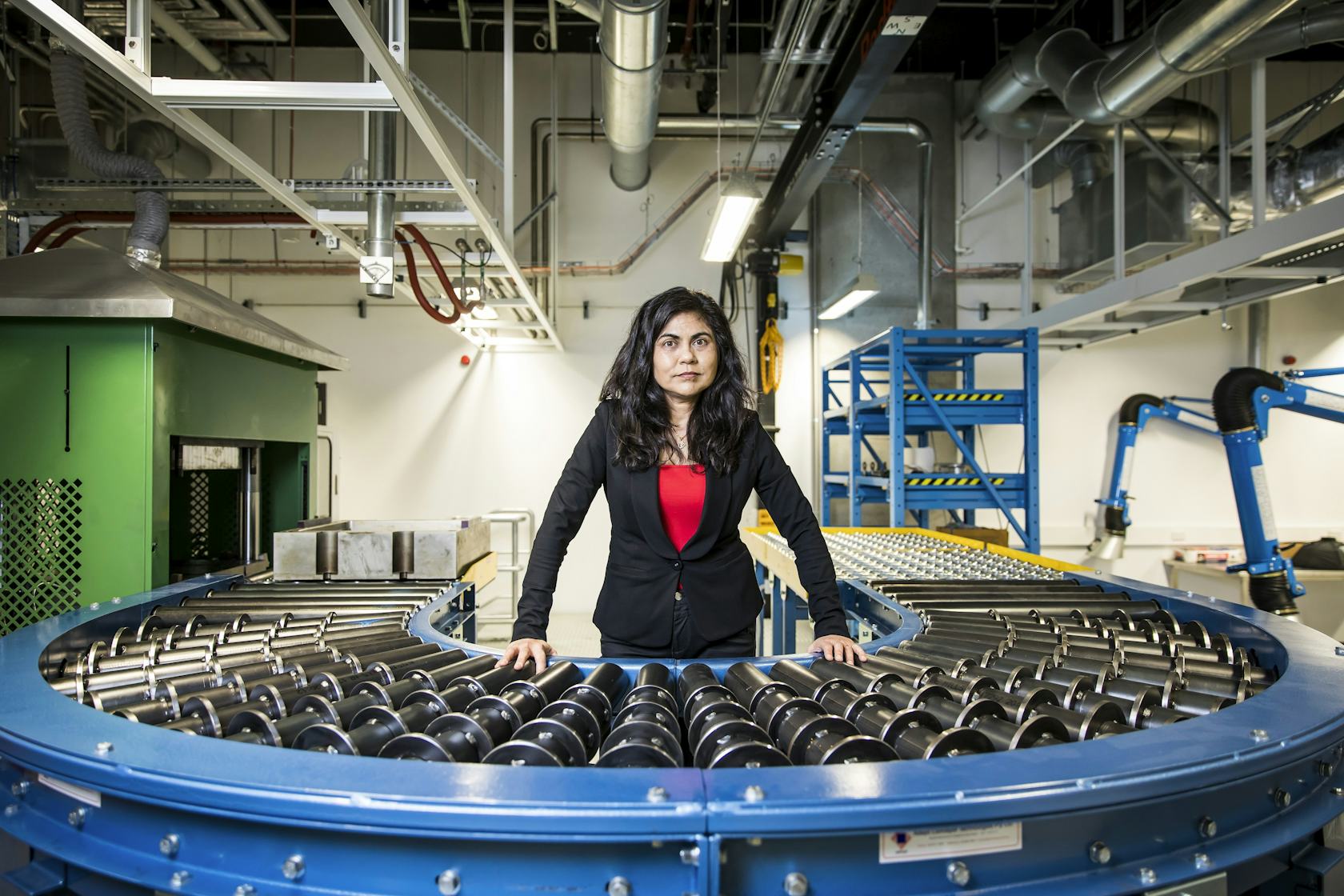

Scientist, engineer and inventor Professor Veena Sahajwalla is a superstar in the waste and recycling industry. Her long list of achievements includes: launching the world’s first e-waste microfactory; developing a ‘material microsurgery’ technique to extract valuable materials from end-of-life electronics; and inventing a ‘green steel’ technology that replaces some of the coke used in the steelmaking process with defunct tyres. Veena is the founding Director of the University of New South Wales’ Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) and heads up the university’s new ARC Industrial Transformation Hub for Microrecycling of Battery and Consumer Wastes.

It goes without saying that Veena is a very busy woman. But after talking to her for just a few minutes, it’s easy to see how she expertly juggles it all. Veena’s brilliance is obvious, she speaks rapidly, ideas bursting out of her, and jumps from one topic to the next, making astute connections with ease. What is perhaps even more noticeable than Veena’s intelligence is her clear passion for recycling science.

“I am a hoarder,” she admits. “There’s so many different things I've got sitting downstairs ... and I’m like, ‘No! My goodness, we can't throw this away’.”

“In my mind [I] picture all the solutions that we could be developing and that whole strategy of reform that I talk about,” she continues. “I'm thinking about how that manufacturing could be done … it’s my head and my heart that work together.”

Through her recycling microfactories, Veena goes beyond the three Rs of the waste hierarchy — reduce, reuse, recycle — and looks at how we can reform waste streams into valuable new products. These modular factories are already being used to turn used tyres into green steel, old clothes into building panels and mixed waste glass into ceramic tiles.

Professor Veena Sahajwalla's vision sees 'MICROfactories' set up in smaller communities to process recycled tyres for significant economical benefit.

“It’s about bringing recycling into that 21st century thinking, if we could imagine a future where everything is being reformed,” Veena says.

She says that our current recycling systems which separate out product by material — paper, cardboard, plastic, aluminium, glass — are not capable of coping with the complex products that we use every day.

“Our computers, phones, electronic devices are [made up of] different materials. We can't expect them to be that complicated and, when it comes to recycling, just expect one thing to solve all the problems,” she explains. “For more complex devices, you need more complex ways of thinking.”

That’s where microfactories come in. Micro-recycling uses a series of small modules or machines to process different materials that make up a product. These factories are adapted to suit the product that needs to be reformed and scaled to suit their location — meaning big cities would need larger factories while regional communities could set up smaller ones. At UNSW, Veena’s microfactories only take up roughly 100 square metres.

Veena explains the process of microfactory recycling using the example of a printer. Like all electronic waste, this product is made up of a complex range of materials: plastic, metal and, in some cases, glass. Microfactories look at how each of these materials can be converted into a new product. The plastic casing of a printer, for example, might be turned into plastic filaments that can then be used in 3D printing.

“You wouldn't want to just put it all in one big smelter, because the plastics would simply burn and you wouldn't be able to ever get that plastic back again,” Veena says. “So that thinking around how we can actually look at different types of plastics, where it's integrated with metals, is not to just see it as: okay, metals have value and plastic doesn't. Microfactories are all about creating these as co-products — a plastic product [and] a metallic product.”

Veena’s appreciation for complex systems can be traced all the way back to her childhood, spent exploring the lively streets of Mumbai.

“I was born in Mumbai [where] there's never a shortage of all the clever things you could be doing and thinking,” she says. “The streets, the factories, the grunge, the mega-population and all the people and the complexity of life, I mean, it's about as complex as it can get.”

Veena thrives on this complexity. Where others might see chaos — a broken phone, with a smashed screen that reveals tiny metal and plastic components, for example — she sees opportunity.

“For me, on a personal level, it's thinking about that holistic and whole of system approach: if you were remanufacturing [something] where could end up? How could it be utilised?” she says. “Not just thinking of one step, saying, ‘okay, we'll collect it, we'll recycle’. But what does that actually mean? It's not really adding any value until it fulfils some purpose.”

Veena’s scientific breakthroughs show us what can be achieved when we approach ‘waste’ with an open mind. By applying the same creative energy to reforming products that we do to creating products in the first place, she is helping transform not just old tyres, clothes and glass, but the entire recycling industry.

National Recycling Week takes place from November 9-13. For more information and to find out how you can get involved, head here.